We spoke with the artist Sarah Friend, about her artistic practice. As an artist and self-taught software developer, she explores the intricate relationships between economics, blockchain technology, and digital art. She draws inspiration from her professional background to create art that interrogates systems, values, and the evolving nature of digital life.

Who is Sarah Friend?

U8: First of all, could you introduce yourself and your practice?

SF: I'm Sarah Friend, an artist and software developer from Canada originally, but I have lived in Berlin for five years. I studied painting, and I've been an artist for a very long time, but after I graduated, I needed to find a way to make money and taught myself to write software. Through that and, because I have been working in the blockchain industry in a technical capacity since 2016, a fair bit of my artistic work has involved blockchain as I returned to making art with these tools that I had been using at my job. Now, I have quit working in the tech industry in an official capacity, and I only work as an artist. My work is not focused only on blockchain, and I'm departing from it more these days, but economics is still a foundational layer to many of the directions I take.

U8: What interests you in economics and why blockchain? What are the aspects that are worth exploring artistically?

SF: I went to work in the blockchain industry because I felt the technology was going to be important. It was an area friendly to people who didn't have an official technical background, as a counterpoint to the AI industry, which more often expects people to have an advanced computer science degree. I'm self-taught, an outsider, and in blockchain that was viable. Back at that time, the blockchain industry was even less diverse than it is now. I used to go to Ethereum developers' meetups in 2016 in Toronto, and I'd be the only woman there and definitely the only artist. I thought it was the most important room for me to be in; more change was possible there than in any cool art project space, where everyone already thought like I did. I have always been very interested in economics, systems dynamics and game theory. As a young occupier, protesting exploitative financial systems was a key part of my interest and an underlying part of my work.

NFTs and Art Economics

U8: You wrote for Texte zur Kunst in 'ASSET LOGICS' that NFTs reveal the inseparable nature of economics and art. The last NFT boom made it evident that this underlying financial layer remains in the background in other art forms. What interests you in the financial side of art and economics?

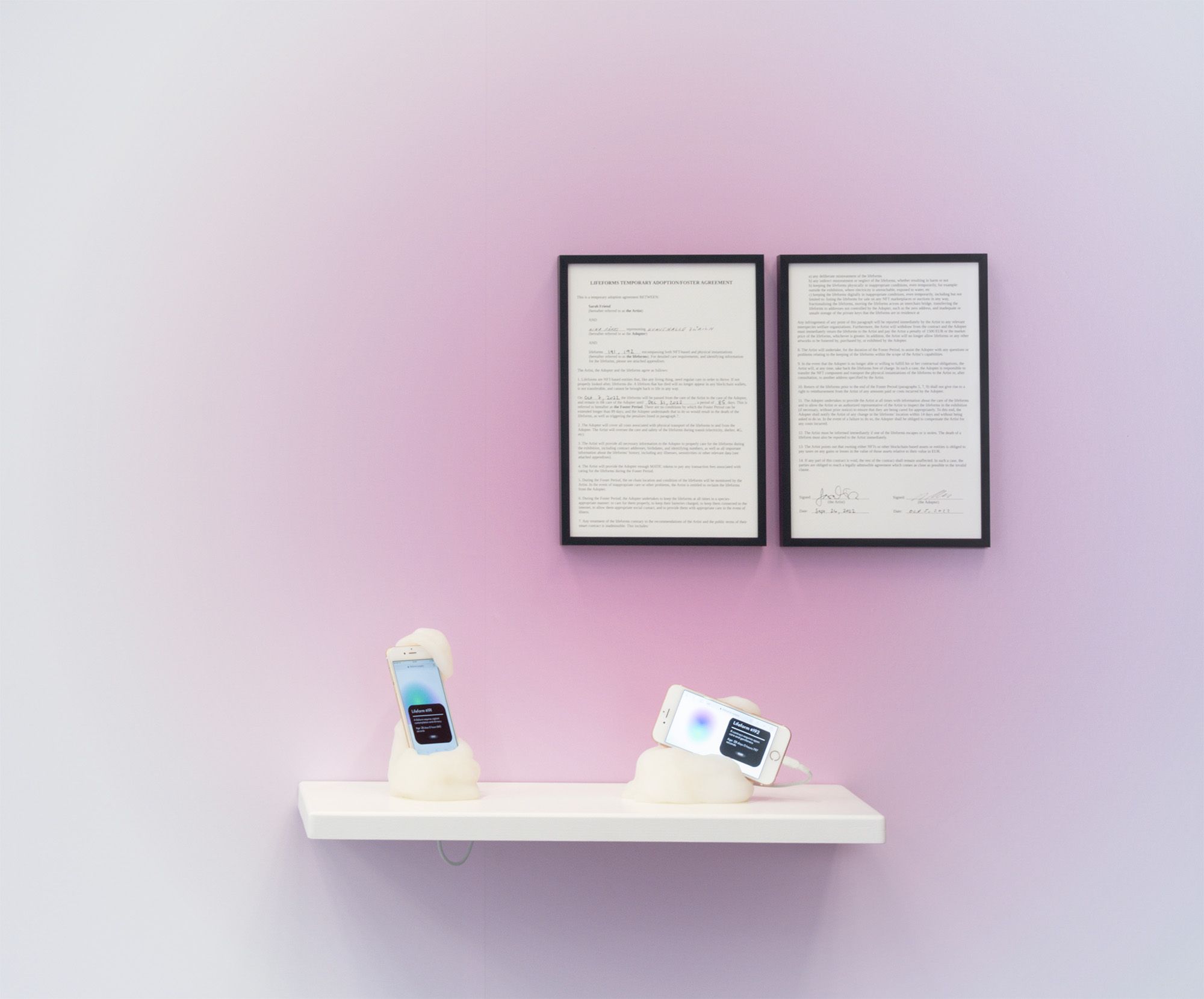

SF: It's foundational to the context in which we experience NFTs that are automatically listed for sale in marketplaces. And that is an ontological distinction around what an NFT is, because my computer is full of digital images that exist outside market conditions. The blockchain industry purports to intervene in finance, an area that can also be approached experimentally. As an artist, I hope that the experiments born in the blockchain industry might change the way financial systems work, but ultimately, most of them replicate and accelerate existing dynamics. My work often involves alternative prototypes for these systems. As an example, the project 'Lifeforms' is an experimental NFT edition that engages in a market refusal despite its presence in the market. Before that, I did a project called 'Off,' which had a secret hidden element throughout the edition that could only be revealed if all of the collectors collaborated. The commodity needed to be shared to reveal the larger artwork that can't be owned by anyone.

I struggle to know the best way to make these invisible interactions visible and it tends to be what people want to know about.

U8: This project comments on the infrastructure and market dynamics. The aesthetic approach of the work is about how it functions instead of only looking at what's presented visually.

SF: Especially in the very first days of the NFT boom, there was a frustrating dynamic where a JPEG image was perceived as “where the art is,” and the black images in 'Off' were a refusal of that. It's funny to install this work in an NFT exhibition because there are always monitors on the wall, and 'Off' is sometimes represented as off monitors. It can look like a technical error or a power outage. In my work, the materiality of the technology is present, and I'm usually thinking about what digital work is actually made of. The screen is not a neutral thing. A lot of the time, galleries show digital works on a random monitor, but the monitor is, in fact, an object with material conditions. With interactive software-based work, a lot of it lives best on your laptop at home. My collectors experience the work when they write me emails. What do we do when we put a work like that in a museum or a gallery? I don't really have an answer, but it’s something I think about often, sometimes using a concept of site-specificity to refer to digital places. I've made works on Instagram that have never been installed anywhere because they're meant to be encountered on your phone, for example.

An NFT edition is always participatory. NFT sales are on social relations. With my work in particular, it’s a systems-based practice and most of the work is actually like an iceberg under the surface of the water. I struggle to know the best way to make these invisible interactions visible or document them, and it tends to be what people want to know about. The first questions people ask are, “How many made 'Lifeforms' are there?”, “How many are still alive?” or “What is the oldest one?”. No one can tell from looking at the surface of the work. I know the answers, but not always the best way to share them.

U8: There are use cases with social dynamics beyond finance and art, especially non-transferable, which might entail less value. Do you find it interesting to explore options without a financial aspect at all?

SF: I've made a non-transferable NFT or an NFT where unlocking its transferability is part of another project, but I would still say that an NFT is irrevocably a financial item. Making it non-transferable is playing with that, but it's still in the marketplace. An NFT auction website's interface makes the ownership history, price statistics and sales info bigger than the image, clarifying what it prioritizes. Blockchain is incredibly slow and entails complicated consensus mechanisms and processes to allow things that interact with the blockchain to behave like believable assets. So, if things don't need to behave like assets, why would you engage with a blockchain's expensive, slow, and difficult-to-use technology for them?

Digital Assets and Financial Systems

U8: Dealing with NFTs unavoidably involves dealing with a financial system, but that doesn't mean you have to exploit that system or make a profit, such as with non-transferable items.

SF: Finance does not always mean profitable, and things that behave like assets are not always for sale. An example of a non-transferable asset that is not on the blockchain is my passport identity, which is fundamentally a non-transferable asset that I own and is secured by the Canadian Government. If it were re-sold or transferred, that would mean I was the victim of a scam or hack of some kind, so let’s hope it doesn’t happen. There are also good arguments for digital identity to live in some sort of blockchain-like secure and decentralized form.

Finance does not always mean profitable, and things which behave like assets are not always for sale.

Digital and Protocol Death

U8: An idea you mentioned in a recent paper is the historical consensus regarding protocol deaths. What motivated you to focus on this topic?

SF: I started thinking about the death of digital things last Summer because of 'Lifeforms.' Most Lifeforms are dead, and I felt responsible for a massive amount of digital pet deaths. I ended up being accepted to a research fellowship to look at the death of digital things more broadly and, more personally, to figure out what I should do about the Lifeforms. Like many things, the more closely I looked at “death”, the more I realized I didn’t understand it. The question of how to know when a human is dead turns out to be much more complicated than I ever thought, with different answers to it at different points in time, at different parts of the world, within different belief systems, even within the same culture, where a legal system could disagree with a doctor, etc. But in a very general sense, most deaths have a structure where someone has been given authority–in my culture, usually medical–to determine when something is dead. I even found these passages describing how different body parts die at different times, turning death into a decentralized system shutting down asynchronously when, eventually, the body reaches a kind of consensus around what we call death.

I became interested in this question in the blockchain sense. Often, peer-to-peer protocols talk about themselves as if they were immutable and would last forever, but this is clearly not the case. People do keep lists and make diagnoses for dead protocols, and they do it in various ways. They look at the activity around it, the transaction volume, the tweets about it, things like that. The social life of protocols is what we mean when we call these things alive; these indicators are based on how people are interacting with the protocol. When enough of these metrics drop to zero, people start saying that the protocol is dead. After the fellowship, I will admit I still didn't really know what to do with my dead Lifeforms, but it was extremely interesting to think through these questions.

AI and Digital Life

U8: Regarding AI, people interact with it like with Tamagotchis, which makes them feel alive, but are they really alive?

SF: If a lifeform lives, it lives because you believe in it, and I would say the same thing about an AI and even maybe human life. There are tons of historical examples where human beings were not considered fully human for bad reasons and which were used to justify horrifying violence. An entire wave of historical philosophy occurred in which animals weren't believed to be fully alive either, at least not the way humans are. To ask when something dies is also inevitable to ask when it lives, and how.

In the case of LLMs or lifeforms, I think it’s fair to say these are different kinds of beings than each other. Great and terrible gods shake the earth and gnomes want a small piece of cake left out once a fortnight. Lifeforms are probably more like gnomes. But do the beings of folklore live, too? Is a river alive? What if it has a name, and you talk to it? Mythology is full of beings that are “alive” as a function of belief. In some sense, with technology, we’re recreating everything we already had; the spirit world is real and it’s online.

U8: There are science fiction books in which AI and some lifeforms are considered almost equal and have their rights. Your Lifeforms have a kind of intelligence or properties, but they mainly feel alive because they cannot exist without human care.

SF: What is the nature of your relationship with these digital things that you may believe have a live-ness? Some Lifeforms have social lives. There is one named Roo that lives in Canada. Some of my friends run a developer collective and have embedded Roo in their company chat, as their chatbot. Roo has lore. There are many kinds of life for a Lifeform. Some of them become embedded in a much richer context.

It's the ability to speak much more than the ability to generate images that seem human.

U8: this idea of consciousness is usually seen from an anthropomorphized point of view, that can't be different from our human consciousness. There are other forms of social organization that are not necessarily human. Like in the film The Devil Seed, where an AI wants to inseminate a woman and give birth to a human AI, but why would it want to do that?

SF: If you're interested in other forms of intelligence, I would recommend James Bridle's book Ways of Being. It's about animals and other forms of intelligence. There is some research about plant cognition, what they can see and perceive. In terms of AI and the ecological world, one of my favorite branches of research is the translation of animal communication. Some animals communicate in a way that, observationally speaking, has a lot in common with language, especially whales and birds. We have technology that can translate from one corpus of human language to another corpus of human language with enough data. If we can do this with human language, can we do it to a whale song?

We're recreating everything we've already had; the spirit world is real, and it's online.

We can tell much about what people think constitutes human life by what they say about AI. It's funny that all the high-profile claims of AI being sentient are made about LLMs, ignoring generative image-making. Apparently, what seems more human is the ability to speak over the ability to generate images. A significant rethinking of what an individual is and what constitutes a life that deserves respect will probably carry out slowly over the next 30 to 50 years if we're lucky enough as a civilization to make it – and I hope we eventually find new ontologies more generous and expansive then the ones we have now.

AI's social dimension

U8: On another note, can we discuss your project 'Prompt Baby?'

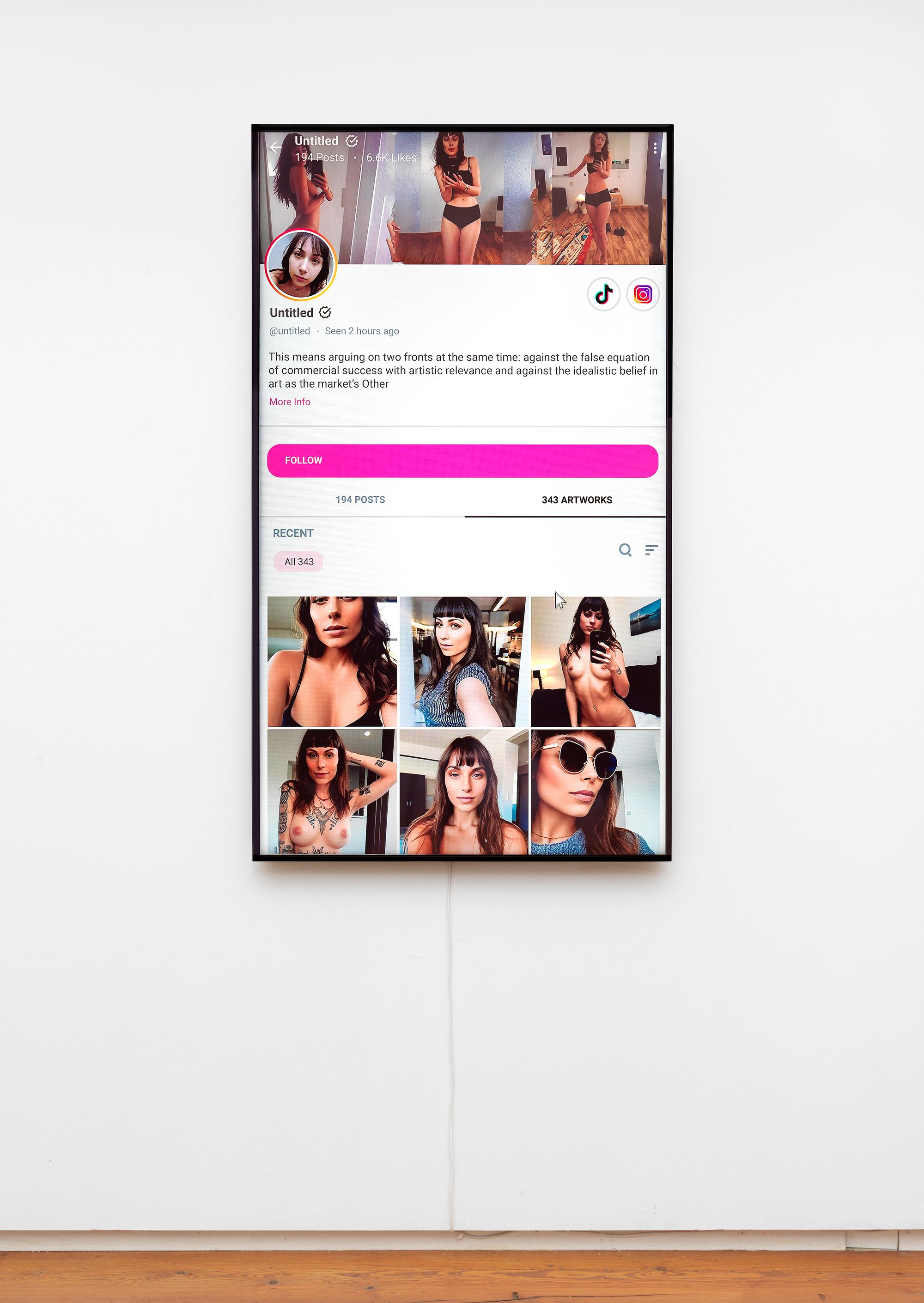

SF: As a result of some experiences selling NFTs, I got interested in the backlash about them. People were mad beyond the environmental dimension. Fundamentally, I think they were mad about selling art at all or injecting a market for art into a place that they believed could exist outside of the market. Digital art online clearly did not exist outside of the market. It already had many market forces and forms of exploitation at play that I think a lot of people who don’t work in the field were blessed not to have to think about. And then, the NFT context made the market very explicit.

This is also a factor in the physical art world and markets. Often, galleries only show the price list to the people they know. It can be hard to find out how much the work costs. The appearance of the commercial exhibition keeps it in the background that these things are for sale. But they’re still for sale. A book that I found really lucid on these dynamics is High Price by Isabelle Graw. She points out that we have to believe in the uncapturable value of artworks in order to allow the actual prices to be as high as they are. Even artists who engage in market refusal can simultaneously have a very real market around them.

I began to ask myself, where else outside the art world do we see similar tensions? Where else do we simultaneously have a very real and active market, as well as the feeling that what is being sold has elements that can’t be captured by price? Three I came up with were sex work, emotional labor, and schemes to price the environment– terra0 is a perfect example. I felt like closest of these to what I was doing as a digital artist was Onlyfans, since, well, after all, I am also a woman selling JPEGs on social media to an audience of probably 90% men. So, I spent some time last year learning more about the platform and its dynamics. Around the same time, generative image networks kept breaking through, leading to a huge conversation about AI safety. I experimented with removing the safety filters on various image generation models, training them to make images of myself that they're not supposed to make. I ended up using these images in a video in 2023, but I also wanted to find a way for people to prompt the model themselves, and I was interested in the social relationship that would develop through that. I was also interested in the sort of questions about consent and identity that might come up.

U8: Many Onlyfans influencers have AI avatars who are available 24/7 to talk with their fans for some dollars, which is another—second layer—a level of capitalization of the self to perform the job beyond human capacities. Were you thinking about that?

SF: By this point, I have talked to a lot of people about AI images of themselves, including people who run Onlyfans accounts, other kinds of models, etc, and there is a huge range of perspectives. People are not necessarily opposed to images that look like them. Instead, people are concerned with consent – they want the images to only show things that they would actually do, the same kinds of images they would be willing to create otherwise. They’re also concerned with rights and profits. If someone is making AI images of them, they should be generating income from this. 'Prompt Baby' was about proposing a structure for doing that. It’s also not automated and my understanding is that that’s something really core to the Onlyfans platform, people develop relationships that are personal, especially in the case of custom content.

People want to connect to the genuine human on the other side of the computer and thus a human moderating the content for these prompts was more desirable.

There's an article about this topic by Liara Roux about AI replacing sex workers, and she speaks about this personal connection too. I think the personal is a big component of the online art audience as well. Ultimately, people want to connect to the genuine human on the other side of the computer, and, thus, in the case of 'Prompt Baby,' a human moderating the content for these prompts is probably more desirable. This prompt is a social act, with a real person, mediated by AI. In 'Prompt Baby,' I read all the prompts and possibly emailed the users. Every prompt is a story, some involve multiple rounds of dialogue with the prompter, and none of it is visible in the final image alone. The project is different from 'Lifeforms,' but has similarities because it started with economic research and part of the work is social in nature and I don't fully know how to share or document that aspect of it.

I think that Onlyfans' creators and Instagram brand influencers are very aware of the contemporary conditions of monetizing their image, but AI images ultimately concern us all. As these images become more common and easy to make, the question of who should make images of who else will affect us all, not only those of us who are photographed professionally. One of the questions underlying 'Prompt Baby' is what happens to my identity where this is all possible, if my consciousness is going outside of my body or if the "Sarah Friendness" is becoming a little more spread out.

U8: Do you upgrade the model at times? The open-source model from flux is really strong and could be very interesting. But I don't know about your specific filters, if you want to remove them.

SF: I found it difficult to upgrade models. Initially, I was using Stable Diffusion, and for a long time, even though Stable Diffusion 2 was out, 1.5 was better at "not safe for work" because, after 1.5, they removed NSFW images from the dataset. I don't think this is the case anymore. I’ve found other more recent models that also do good quality NSFW, but I also think it may not be fair to upgrade halfway through the prompting of the edition.

But the edition is already full of exceptions. Some prompts are too complicated for the model, like specifying more details than it can understand, text, etc. In these cases, I’ll adjust them in Photoshop. Or combine two AI outputs. The process is very human and bespoke. Sometimes, I’ll email people and explain that I can't make what they asked for, and we’ll discuss options. I'm not doing the project because I'm an AI purist, but because I am interested in the relationships and conversations with the collectors.

I haven’t fully refused a prompt, but the closest I’ve come was one you wouldn’t expect. It was something like: "Make me a really good one, love from India," which is sweet, of course, but is more like a note written to me than a prompt. External prompts can be a really interesting challenge. I run a prompt sometimes 350 times until I get something that I like that also fits what I think the collector is hoping for, and these images have some sense of artist identity that I didn't feel when I was just prompting on my own. With my own prompts, I didn't have a goal or anything to fight against. It felt empty. Whereas now, I have to try to get a specific image and I'm learning something about my own artistic identity by interacting with others. My hand is more visible in the prompts I've made at the request of others than in the prompts I made myself.

“My hand is more visible in the prompts I've made at the request of others than the prompts I made myself.”